Project partner John McCrory wrote the following piece for our exhibition project guide. We hope to be posting out some copies of the guide to local people, but here’s a sneak preview of what you can expect to find.

Given the demand for housing after the First World War, and scarcity of suitable land in Manchester, Burnage was a prime site for redevelopment. In 1923 the City Surveyor arranged for the purchase of 78 acres from Lord Egerton of Tatton, enough for 620 houses, and Burnage was transformed forever.

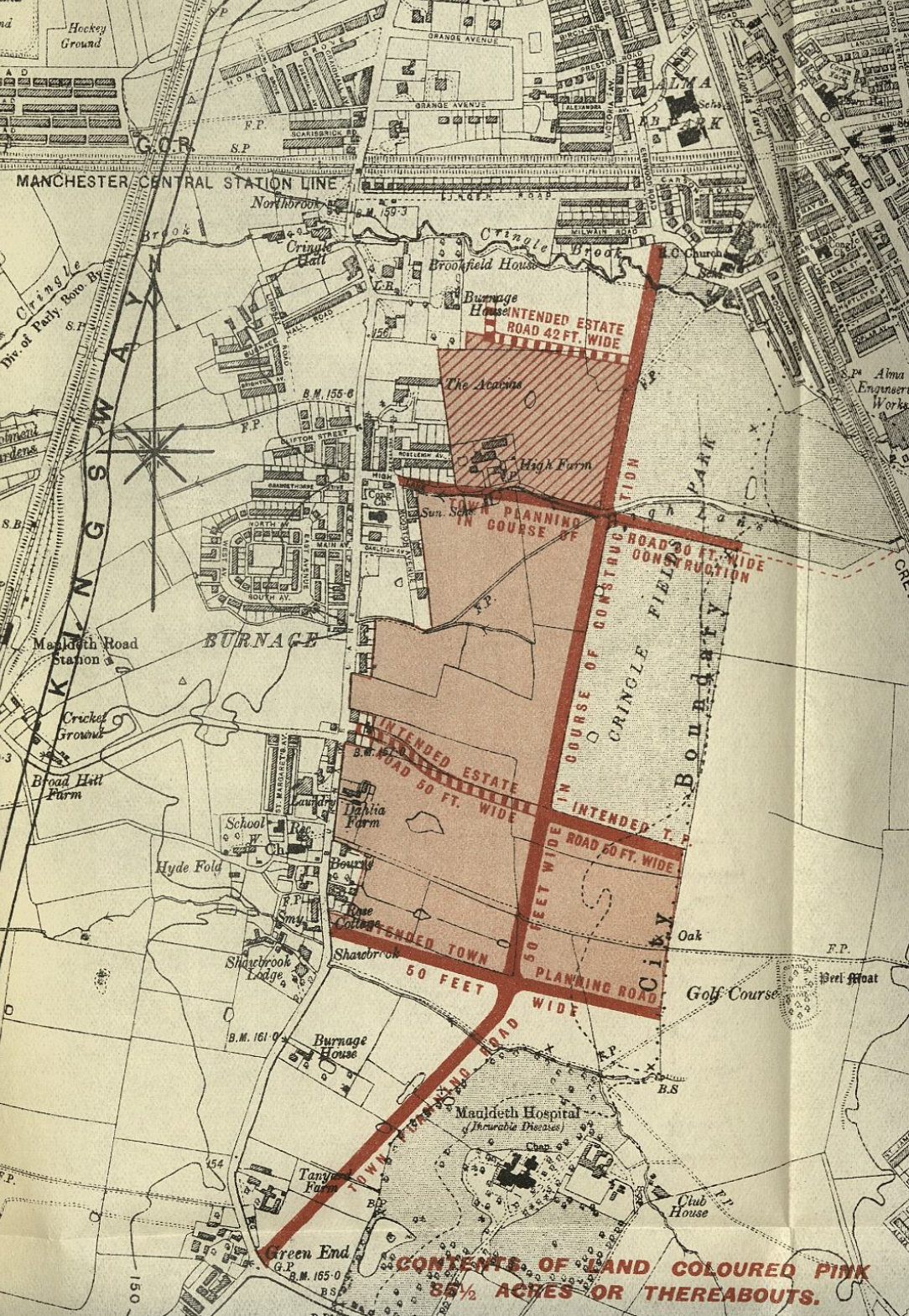

From the Appendix to the City of Manchester Council Proceedings, 1922 – 23.

Plan showing Errwood Road running north to south- an unemployment relief work scheme from the early 1920s- with the fields and farms the Corporation bought from Lord Egerton to build the Burnage Estate.

The houses were subsidised by the Government and built to the high standards set out in the Government’s ‘Tudor Walters’ report, which stipulated there should be no more than 12 houses to the acre. In the ‘cottage’ style they were to have sizable gardens, allowing for maximum light and ventilation, privacy, space for growing food, and safe places for children to play. Every house would have three decent sized bedrooms and an indoor toilet.

Diagram from How Manchester is Managed: a record of Municipal activity, (1926)

The Burnage Estate [45] was the first of six such developments in the area between the wars:

Burnage Extension Estate (264 houses) [47], Kingsway Estate (1392 houses) [44], Ladybarn Estate (1100 houses) [50] and the Green End Estate (354 houses) [48]. In 1934, 62 extra houses were built for people moved from demolished inner-city areas [46].

Diagram from How Manchester is Managed: a record of Municipal activity, (1926)

Later housing acts would reduce minimum room sizes, but Manchester prided itself on maintaining its own, higher standards. Houses were separated from main roads by landscaped trees and verges, and ‘cul-de-sacs’ were used to minimise both traffic disruption and construction costs. The earliest developments in Burnage also featured separate playgrounds.

Ordnance Survey (1935) Lancashire, sheet CXI.8 (Manchester; Stockport), 25 inch to the mile. Showing vacant areas filled by the final phase of the estate. 64 families displaced by the ‘slum-clearance’ programme

Construction was initially slow, caused by a severe shortage of labour. At one point only four bricklayers and five apprentices were employed to build 620 houses! Eventually, the Manchester Corporation used a combination of small and large private builders, and its own ‘Direct Works’ labour force, to complete the estates.